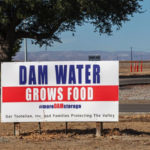

(NEW YORK) — The industry that overwhelmingly uses the most water resources in the West does so for good reason: to provide sustenance for the rest of the country.

Globally, the agriculture sector uses 70% of all freshwater withdrawals. In California, that number is ever higher — at 80% of the state’s public water supply — and farmers are being forced to transform the way they cultivate crops as megadrought that has been plaguing the region for decades intensifies.

California is the nation’s fruit and vegetable basket and grows hundreds of commodities. But about a third of that water is used to grow just three crops: almonds, pistachios and walnuts — industries that amounted to about $9.5 billion in exports in 2020 — nearly half of the state’s total, according to the California Department of Food and Agriculture. Almonds, which use about 1.1 gallons of water to grow just one nut, according to Pennsylvania State University, and account for about 10% of the state’s water use alone, Arohi Sharma, deputy director of regenerative agriculture for the National Resource Defense Council, a nonprofit, told ABC News.

As a warming planet threatens to worsen drought and heat conditions in the West, farmers may be called to grow the crops that will be most resilient in the changing climate, Sharma said. That could include lessening the amount of land and water dedicated to “thirsty nut orchards,” she said.

Planting nut trees at the height of the drought

Tree nuts are an extremely valuable crop, with growers making a “pretty penny” by selling them, Sharma said. Out of California’s $20.8 billion in in agriculture exports in 2020, three of the five most common exports were almonds, pistachios and walnuts, data from the California Department of Food and Agriculture shows.

In addition, the almonds are shelf-stable for about two years, Richard Waycott, president and CEO of the Almond Board of California, told ABC News in an email.

Using figures from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Sharma calculated that during the height of the last drought, between 2012 and 2017, farmers planted more than half a million acres of new nut trees. Sharma believes the additional plantings were a result in the rise in value of the commodity, combined with the lack of legislation in California that bars farmers from planting drought-intolerant food crops.

“And without limits or caps on water use, growers will take whatever water they save to simply plant new nut orchards,” Sharma said, adding that it will ultimately be government oversight and the implementation of new policies to force the agriculture industry to conserve water.

Those almonds, pistachios and walnut groves have now grown to more than 2 million acres of land in California — out of the state’s 43 million acres used for farming — creating a “disconnect” between the availability of water and the number of acres that are being planted with “these water thirsty, drought intolerant crops,” she said. California almonds had two record shipments in 2020 and 2021, with “steady, significant growth in the years before,” Waycott said.

California, with its Mediterranean climate, is one of the five places on Earth where almonds “can grow at any scale,” Waycott said. The almond industry has been working for decades on making the industry as sustainable as possible, he added, including the development of micro-irrigation now used on 85% of almond orchards in the state, compared to pre-1982 practices that involved flooding the fields or using large sprinklers.

Almond farmers in California have since reduced the amount of water needed to grow each almond by 33% and is committed to another 20% reduction by 2025, Waycott said.

“While almond farmers have made strides on irrigation efficiency, further improvements are underway,” Waycott said.

Reducing water while sustaining crop output

The challenge will be to reduce some of the agricultural land devoted to these crops and make the farms sustainable so they may continue providing jobs and food for the rest of the country, Pablo Ortiz, climate and waters scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, told ABC News. In California’s Central Valley, the low-flow drip irrigation technology that was implemented by farmers there did not save water in the end because they instead used the conserved water to cultivate more crops, Ortiz said.

“So, this deployment of technologies needs to be contained by some other policies that would allow you to actually reduce water usage,” he said, instead of using conserved water for other purposes.

The agriculture industry is one of the many sectors in California that are suffering from an antiquated water sector, experts say.

The infrastructure and business models, many implemented in the 1900s, were not created with the forecast of climate change or water shortages. The system of water rights, or legal rights to extract and use a quantity of water from a natural source based on where the property is located, as well as policies such as the California State Water Project and the Central Valley Water Project, which collect water from rivers and redistribute it to cities through a network of aqueducts provide an advantage to some, Sharma said.

“And now we’re facing the repercussions of these very old inequitable water rights systems and water infrastructure,” Sharma said.

The upshot is that farmers, especially longtime landholders are prioritized over other water customers, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Decentralizing water a potential solution

Robert Bartrop, head of global business development for SOURCE Water, a company that builds custom solutions for water needs, told ABC News he envisions a future in which the water industry decentralizes, in a way similar to the telecommunications and energy industries. In that case, investments would be made to redesign the grids to more efficiently distribute water.

In order to prepare for a future with less water, California, and the West as a whole, will also need to transform its water usage in a way that invests and supports its agriculture industry, Sharma said.

Part of this entails ending the practice of massive single crop farming, which depletes the soil of nutrients, Sharma added.

Instead of growing one or two crops over thousands of acres, farmers are starting to grow a variety in 20-acre tracts to protect the health of the soil and prevent erosion, which will make it so farmers, including those who are reliant on the cultivation of tree nuts, are less reliant on one income stream as well, she added.

Farmers will also need to adapt new regenerative solutions, such as building soil health as a drought resiliency tool so that it can hold onto more water despite being watered less, Sharma said, describing regenerative agriculture as a “holistic approach to land management.”

“We need to start diversifying what’s grown on the property as a way to regenerate ecosystems, as a way to fight drought and pest pressures that are coming as a result of climate change,” she said.

The source of the water is important too, Bartrop said. Farmers will need to be more efficient with using recycled wastewater, or gray water, for their irrigation needs, as there is currently too many resources wasted on making water used to irrigate crops and feed livestock potable, he added.

Groundwater, which the agricultural industry in California has been depleting over the past century, is not the solution, Ortiz said.

“With water scarcity and climate change, it’s important to know this isn’t an emergency event,” Bartrop said of current drought conditions and the threat of water scarcity.

Copyright © 2022, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.